Dunham Tavern’s Cistern & Smokehouse

Duncan Virostko, Museum Assistant

To keep a Tavern, it’s not enough to just have a taproom! The less glamorous structures that made up the Dunham Tavern complex were just as important to its function as the larger home and business which still stands today. Some of these supporting buildings have survived, whilst others were relocated and removed. Both the Cistern and the Smokehouse at Dunham Tavern presented interesting mysteries to historians that have now largely been solved.

Recent research has finally made sense of the system that Dunham Tavern once used to supply water, and it has taken a combination of documentary, photographic, and archaeological evidence to reconstruct it. For the final piece of the puzzle, we can thank Dr. James A. Stephens himself, who lived with his family in Dunham Tavern c. 1890-1930, for helping make sense of the confusing combination of outbuildings and architectural features both extant and long gone. The photographs below gives us our first clues about this system: a cistern, still extant in 1938 during the Dunham County Fair event, was located to the side of the original barn (built in 1840, burned in 1964) and in line with the small stone outbuilding which still stands behind the tavern.

Rear View of Cistern, 1938

Cleveland Press Collection, Michael Schwartz Library,

Cleveland State University, 1938

Side View of Cistern

Dunham Tavern Museum Scrapbook, 1938.

The rough and simple stone work, with various sizes of stones, is of the same type as the small stone building behind still standing behind the Tavern, indicating that both are of the same period. The fact that such stones, rather than more regular dressed stones or brick were used for both structures, indicates that they were both built early in the Tavern’s life, perhaps before regular stone quarries in the Cleveland area had been established.

Archaeological excavation of the remains of the cistern, apparently rediscovered accidentally as the result of running electrical conduit, indicate that it went out of use sometime around the turn of the century, as indicated by dating evidence found during excavations: a Sewing Machine Sperm Oil bottle dating to circa 1894, and a beer bottle marked Cleveland and Sandusky Brewing Co.; which cannot date prior to 1897 when that company was created as a result of the merger of 11 Northern Ohio breweries. As the archaeological found example has less ornate logo typography than other surviving examples, and because Cleveland & Sandusky Brewing ceased operations in 1919 as a result of Prohibition, it cannot be from later than the 1910s. As the newest artifact found within the cistern, this bottle shows the cistern was filled in at this point, probably commensurate with Stephens’s modernization of the house and the installation of more modern plumbing.

Smokehouse & Rear of Dunham Tavern, ca. 1932

Cleveland Press Collection, Michael Schwartz Library, Cleveland State University, 1932

In his letter of 1930 to Charles Asa Post on the history of his home, for the book Doan’s Corner and The City Four Miles West, Dr. James A. Stephens finally explains how the Cistern at Dunham Tavern functioned: “It had a water tank connected with an outside cistern into which water was forced with a force pump, also a lead bathtub.” The “outside cistern” he mentions is the structure seen in the pictures from 1938. This was connected via lead piping, the remnants of which were found archaeologically, to a water tank fed by a hand driven pump. It’s unclear where this water tank was, though given the description of the cistern as “outside”, one presumes it was located somewhere within the house, possibly in the cellar. The location of the pump is also obscure, although regardless of its location, to draw water from the cistern into the tank must have taken considerable pumping!

This information is confirmed and expanded on by a passage in Kathern Gil Brook’s book, Dunham Tavern, published in 1938, the same year these photos were taken: “Not far from the laundry door was an old well from which, in the early days water was pumped by means of a force-pump to fill a tank which was connected with a lead bathtub. Dr. Stephens had the well filled up and the well curb was moved to it’s present location at the back door.”. This final piece of the puzzle fully explains the cistern’s history.

Initially, as indicated by the archeological finds, the cistern was located outside the present day back door of the rear wing of the tavern, between the small stone structure and the house. This would have placed it close to the kitchen in the rear wing of the tavern, and made drawing water via the pump more convenient.

This arrangement lasted until Dr. Stephens grew tired of having to manually pump water into his house, sometime around the turn of the 20th century, and he had it filled in. Not wishing to destroy the picturesque curb (the above-ground stone structure) of the cistern, he had it relocated to a spot near the side of the original barn, which would be underneath the current barn. It then stood there until sometime after 1938, when it was demolished.

Smokehouse Exterior, 2024

The 1930 letter from Dr. Stephens also seems to provide the oldest source for the description of the small stone building behind the Tavern as a smokehouse: “... an old stone structure in the rear of the house, still standing, was for smoking meats.” Although for some time erroneously called “the springhouse”, it was never a part of the water supply system, which is why the good doctor mentions it as a separate building apart from the Cistern.

The position of the outbuilding relatively close to the North Wing of the house, which is the known primary center of cooking, also shows its connection with the kitchen facilities. The form of the building does not preclude its use as a smokehouse: although it lacks a chimney, smokehouses of a similar era also lack such a feature. The process of smoking entails a smoldering, rather than blazing, fire which would release smoke only gradually. Traditionally, the smoking of meats took place during the winter months, as a way to help preserve the meats. Green wood and corn cobs were frequent sources of fuel for such fires, as these burned slowly and with a large amount of smoke. Too much oxygen ingress was undesirable, as it would cause the fire to burn too quickly, for this reason a chimney creating a draft would have been undesirable. Smokehouse beams have often been inundated with salt and discolored by smoke as a result of cooking salted meats.

Smokehouse Interior, Showing Beam with Meat Hooks & Smoke Stains on Ceiling, 2024

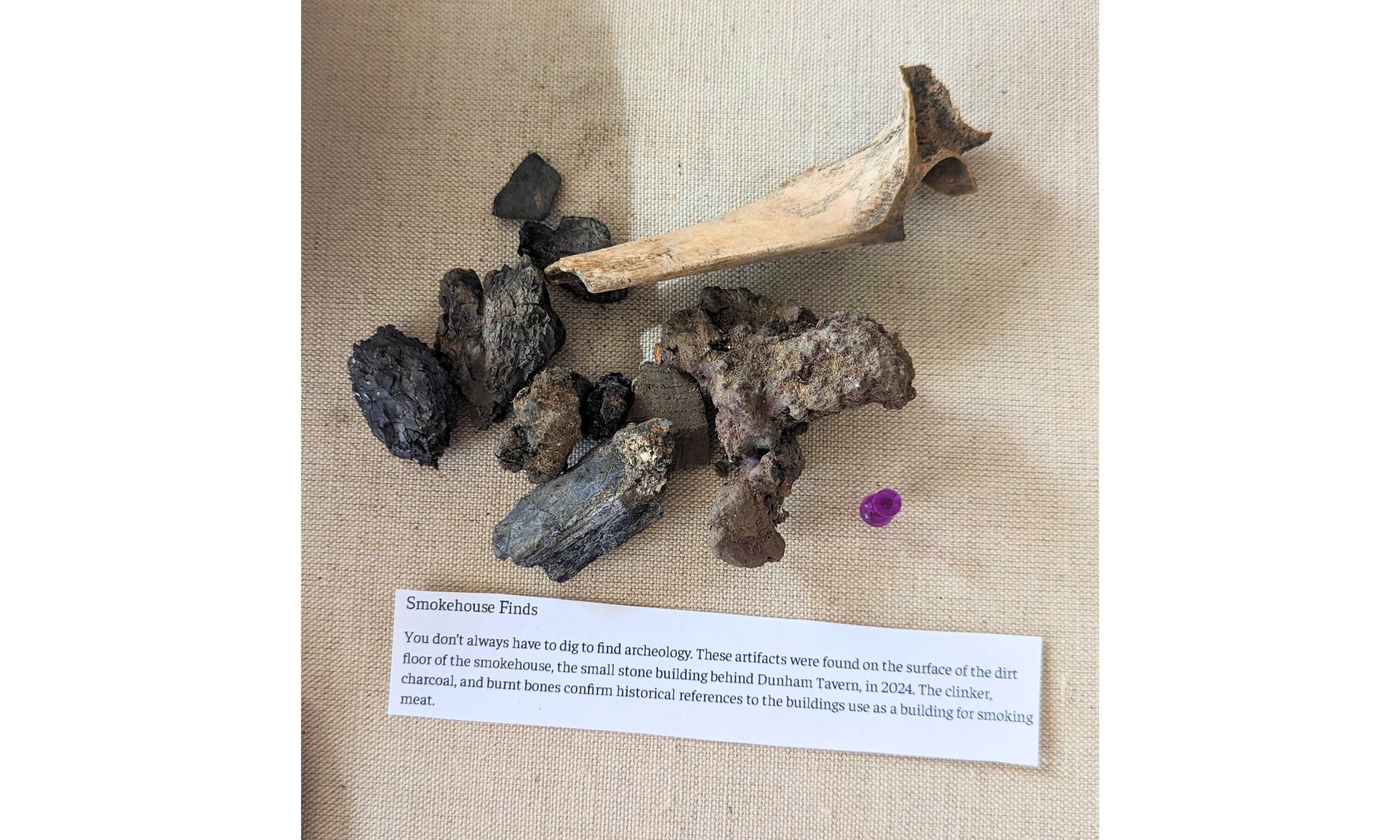

Archaeological and architectural evidence recently examined clearly shows the use of the building as a smokehouse. Architecturally, its heritage is most evident in a large beam, with hooks for hanging meat, which is located roughly in the middle of the building. It is covered in a heavy layer of soot, and discolored. Additionally, its texture is slightly spongy, an indication of salt inundation. Other beams in the roof truss of the building also exhibit similar discoloration. Archaeologically, lying on top of the dirt floor beneath the beam, a series of artifacts were recovered which also affirm the usage of the building as a smokehouse. Two fragments of burnt bone, several pieces of charcoal, and unburned wood were found at this location, pointing to its use for meat preservation. The bone fragments were also consistent with other fragments found at Dunham Tavern during archaeological digs in 1984, 1987, and 1992. This implies that this meat was preserved, cooked, served, and then discarded all on the same site. Near the door, several chunks of clinker (the metal impurities leftover from burning coal) were found which also attest to significant burning taking place on the interior of the building. Interestingly, several chunks of lime were also recovered from this area. This is likely the remnants of lime mortar preparation, and these chunks of lime were produced by burning limestone in a temporary kiln, presumably in the smokehouse. This shows that the building has historically had multiple uses, in line with the smoking of meats taking place only in the winter months.

Smokehouse Artifacts, on display as part of the In Situ: 40 Years of Archeology at Dunham Tavern Exhibit

The smaller structure behind this building, also a smokehouse and sometime incorrectly called a bake oven, is a later addition dating to the mid-1930s: it is not present in views of the Tavern ca. 1932, but is visible in aerial views dating to the 1938 Country Fair. The bricks used in its construction were also used to repair the older smokehouse it, as its stonework was visibly cracked and in need of repointing as can be seen in the 1932 view. Presumably, this was part of the initial efforts to restore Dunham Tavern in 1936 under the direction of A. Donald Gray, I.T. Frary, and other members of The Society of Collectors. Being now 80 years old, it is almost as historic (and aged) as the building it was constructed to replace! The existence of two smokehouses of different periods has confused previous authors writing about Dunham Tavern’s history, and led to the questions which prompted the latest research.

1930s Brick Smokehouse

Aerial View of Dunham Tavern, County Fair, September 15th, 1938

The two smokehouses are visible beneath the large tree behind the rear wing of the Tavern. The two building were built of different materials and during different periods but had the same use, confusing later historians. A small stove pipe, now gone, is just barely visible jutting from the rear of the brick building.

Cleveland Press Collection, Michael Schwartz Library, Cleveland State University,

Sources:

Brooks, Katherine Gill Dunham Tavern. Cleveland: Artcraft Printing Company, September 1938, Pg. 38

Post, Charles Asa, Doan’s Corner and The City Four Miles West, Cleveland: The Caxton Company, 1930, Pg. 105-105

https://clevelandmemory.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/press/id/13161/rec/21

https://clevelandmemory.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/press/id/13138/rec/24

https://clevelandmemory.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/press/id/9364/rec/52

https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/Foundation/journal/Winter04-05/smoke.cfm