Don’t Judge A Book By It’s Title

Duncan A. Virostko, Museum Assistant

“Live Free Or Die!” ~ General John Stark, in a letter to New Hampshire veterans of the Revolution, 1809

It is a pleasure to once more put pen to page, so to speak, for Dunham Tavern Museum. In truth I have also been writing several other articles for our blog, which I hope you are all eagerly awaiting. But this is the one which I felt ought to go to press first, as it meets the present moment best.

Language, by its nature, is a changing thing. As our society changes, so does what is offensive and inoffensive. This can lead to linguistic innovations and rediscoveries, such as "African-American" or the recent return of "they” as a singular pronoun.

Hence my admonition “don’t judge a book by its title": the subject of today’s blog is a review of the 1969 book Memorable Negroes In Cleveland’s Past. The term in the title was at the time of publication still considered respectful, although it was passing out of favor. Given that the book was created by the NAACP, however, it was only natural that it would be chosen for the title. To the modern reader, it is more than a bit off-putting. For their sake, in this review I’ll simply abbreviate the title to Memorable; which the book most certainly is!

In spite of the title, Memorable is more than worth the read for those curious about Black history in Cleveland, especially its earliest chapters .The book covers the history of the Black community in Cleveland from its first survey in 1796 up until 1969. It includes profiles of twenty-eight prominent men and women, an especially progressive choice during the 1960s when even the Civil Rights movement was not immune to sexism. The figures spotlighted by the book represent the best of Cleveland’s past, including artists, teachers, librarians, civil right and social activists, lawyers, politicians, doctors, and businessmen.

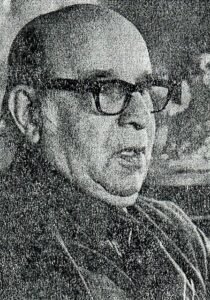

Russel H. Davis (1897-1976)

(Bratenhal Historical Society)

Author Russel H. Davis himself ranks among these local luminaries, having been a longtime Cleveland Schools educator and author not only of this small work but also Black Americans in Cleveland from George Peake to Carl B. Stokes, 1796-1969, published in 1972. Davis was born October 29, 1897 to Jacob Davis and Rosalie Dite-Davis, a postal worker and a French woman respectively. His brother, Harry Edwards Davis, was a lawyer and Ohio State legislator. Russel H. Davis initially earned a degree in education for Western Reserve University in 1920. Two years later, he gained a degree in chemical engineering from the Case School of Applied Technology. He then worked for five years at the Grasselli Chemical Company. In 1928, he finally gained an appointment as a teacher at Kennard Junior High, beginning a long educational career. He subsequently earned his master’s degree from Western Reserve University, and would go on to serve for twenty-five years as principal of various Junior High Schools in the Cleveland public school system before retiring in 1965.

Alongside his older brother, Davis was a significant community leader. In 1943 he spearheaded a commission which investigated the needs of the Central neighborhood, then one of the oldest, largest, and poorest of African American neighborhoods in Cleveland. The study highlighted the dire needs for better housing, schools, recreational facilities and social services in the area and pressured the city for reforms. He also served as a trustee and treasurer for the Karamu House, the historic Black theater and art collective. Davis also served as a member of the male advisory committee to the Girl Scouts of Cleveland. Davis passed away on November 14, 1976, but left behind a significant legacy of social leadership and reform, as well as being one of the first modern academics to write on Black history in Cleveland.

Sara Lucy Bagby, Kenneth E. Snipes, 1969

The illustrator of Memorable is equally worthy of praise. Often, one's private talents are outshone by their more public achievements, and this is the case for Kenneth E. Snipes. He is best known for later leading Karamu House as its Executive Director, a role he held until 1975. Snipes was serving as Art Director & Supervisor of Art Education Programs at Karamu House when Memorable was published. Because of his important and central role in leading African American art programs and artists in Cleveland during the 1960s and 1970s, his own works as an artist are perhaps not so well known . In fact, Snipes was a talented artist in his own right, having earned his art degree from the esteemed Philadelphia College of Art. He was mainly a print artist, and this is reflected in the prints he contributed to Memorable. His artwork was invaluable: a number of early historical figures had no images available for use as illustrations for the book. Yet of course, for any book about people it is important that the reader be able to see their faces. Many of his depictions thus went on to become the standard image of certain historical figures. This is true, in particular, of his illustration of Sara Lucy Bagby. It must be said, however, that it does not seem a particularly good likeness compared to the photograph from which it derives, which on close inspection shows a woman of much finer features. One presumes this is the result of Snipes having to work with a murky copy of the photo, as the face is already well shaded and largely obscured. Memorable thus serves as a showcase for Snipes underappreciated talents.

Of course, since 1969 more modern and in-depth scholarship on the African American community in Cleveland has emerged. Much of Davis’ groundbreaking work has thus been superseded. reinterpreted, and expanded upon. Scholars today have access to far more research than Davis, and more available evidence as well. Modern studies of African American Cleveland history pull from a greater variety of sources, including oral history and art, and digital archives allow researchers to more easily search through the many Black newspapers which called Cleveland home to investigate the rich heritage contained in their articles, ads, and illustrations.

Yet Memorable still has two great strengths when compared to more modern scholarship. Firstly, its brevity. Unlike myself, Russel H. Davis was a master of brevity. Thus his is work more accessible to the casual reader interested in Black history than others’ work which was rather more dense. While not where one’s research journey ought to end, Memorable is therefore an excellent point at which to begin. For the same reason, it makes for an excellent quick reference as well, being more reliable than online sources albeit now quite dated. As a starting point of more modern histories of African Americans in Cleveland, it is also a good work to examine if you are interested in historiography, or the history of writing history.

The Great Migration of the 1920s brought an entirely new, and much larger, community of African Americans to Cleveland. Much of the present community can traces it's roots back to this time. As a result most modern scholarship focuses exclusively upon them. But they are only the most recent chapter of a much longer and richer heritage.

Where Memorable still shines is in being, along with its sister work Black Americans in Cleveland from George Peake to Carl B. Stokes, 1796-1969, one of the few books which focuses on the history of the African American community prior to the American Civil War in Cleveland. Most notable of these early settlers, highlighted in Memorable, were John Malvin (1795-1880), Alfred Greenbrier (1808-1887), Madison Tilley (1809-1887), Justin Miner Holland (1819-1887), and Sarah Lucy Bagby Johnson ( ca. 1843-1906). Their stories are instructive, shedding light on the complexities of race and discrimination in the United States in the 19th century.

Malvin, for example, was the son of a free mother but an enslaved father. Under the laws of Virginia, where he was born, this technically made him free by birthright from his mother, and yet he was forbidden to read, having only the Bible and an older literate enslaved woman as a teacher. Malvin would subsequently move to Ohio in 1827, enticed by the Northwest Ordinance which forbade slavery in the new states formed from its territory, settling initially in Cincinnati. Yet, he would find discrimination in Ohio as well, and would subsequently become involved in the Underground Railroad to move African Americans to Canada. He eventually settled in Cleveland, it being rather more enlightened than Cincinnati. Notably, he was a mariner, serving as owner and captain of the Ohio & Erie canal boat Auburn, and later master of the schooner Grampus, which brought limestone to Cleveland from Kelly’s Island. Using these connections in shipping, he became an important operative for the Underground Railroad, helping fugitive slaves escape to Canada. He also served as a sawmill engineer, a role which Rufus Dunham played in the early 1820s. Malvin promoted public education for Black children in Cleveland by collecting funds to hire a teacher for them in 1833, and later spearheaded the School Fund Society for the same purpose on a statewide level in 1835. During the Civil War, he also attempted to form a company of Black militiamen to serve Ohio, the services of which were declined by then Governor David Todd. Subsequently, these men joined the 55th and 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry (of Glory fame). In 1879, Malvin wrote an autobiography, now freely available on Google Books. Upon his death on July 31st, 1880, Malvin was laid to rest in Erie Street Cemetery, and some 14 inches of newspaper column space were devoted to his life in the Cleveland Leader.

Alfred Greenbrier was also born into precarious circumstances, as what we would call a mixed race man, the son of a White father and Black mother. He arrived in Cleveland on horseback from Kentucky in 1827, a fugitive slave. Greenbrier was an accomplished horse breeder, a skill which he quickly put to use as a conductor on the Underground Railroad, using his swift steeds to spirit escaping slaves to safety along the roads between Richfield and Cleveland. He was never discovered, although strongly suspected by authorities. In addition to these underground activities, he was also active politically as a member of the Abolition Party. Greenbrier’s tale shows that even individuals with a lighter complexion prior to the Civil War faced strong racial discrimination. One of Greenbrier’s residences, purchased after the Civil War, still stands today in Ohio City, and was extensively renovated in 2016, thanks to research from the Cleveland Landmarks Commission discovering its significance preventing its demolition.

Madison Tilley served as an early political leader and activist in Cleveland. He born in Murfreesboro, Tennessee in 1809 and arriving in Cleveland in 1837. He was married in Chillicothe, Ohio and had a family of eight. A powerful orator although illiterate, Tilley recognized the importance the power of voting held for minorities. A favorable Ohio State Supreme Court decision meant that people of mixed race were able to vote in elections, and thus Tilley became a prominent Whig, later Republican and finally Democrat politician in Cleveland. Rufus Dunham no doubt would have crossed paths with Tilley, both being major figures in the local Whig Party. Tilley was also a prominent businessman, an excavation contractor who owned 20 wagons and 40 horses, and employed up to 100 laborers in an integrated workforce. Tilley died in October of 1887, from a case of dropsy, known to us now as an edema, leaving behind his four surviving children.

Justin Miner Holland was a comparative latecomer to Cleveland, and yet he is perhaps the most interesting of the four men because his significance is tied to his artistic talents. Holland was born in Norfolk County, Virginia, in 1819. In 1831 his father, Exum Holland, died, and he moved to Boston, Massachusetts, settling in nearby Chelsea in 1833. In Boston, he met Spanish guitarist Signor Mariano Perez, and started his musical education. In 1838, he traveled to Mexico intending to study under Spanish guitar master Aguado Giuliani Sor, and spent two years learning Spanish. A gifted young man, he was subsequently admitted to Oberlin College in 1841, then one of the few in the United States to educate both women and persons of color. Holland studied flute and composition there for two years, but never finished his degree. Instead in 1845 he married Daphne Howard Minor, and moved to Cleveland.

Holland was a prolific composer, producing no fewer than 300 arrangements and 35 original pieces throughout his career. Holland was also renowned as a guitar teacher, and produced Holland’s Comprehensive Method for the Guitar in 1876. In addition to his musical talents, Holland was also a polyglot, speaking fluent French, Italian, and Spanish. A lifelong Mason, Holland had international Masonic contacts with Peru, Portugal, Spain, France, and Germany. A truly international man, he once even managed to be profiled by a publication in Vienna, Austria in 1877. Holland’s life and career illustrate the complex and international world in which 19th century Black Clevelanders lived. Moreover, his virtuosity in guitar and in composing show how art can transcend borders and prejudice.

Sara Lucy Bagby, ca. 1862, Cumberland, Va. (Library of Virginia)

Finally, Memorable profiles Sara Lucy Bagby, whose life illustrates the widespread Abolitionist sympathies of the people of Cleveland, and how this clashed with official government policy before the war. In October of 1860, Bagby came to Cleveland via Pittsburgh seeking safety, and found employment as a maid. She was only 17 at the time. She and her mother had first been purchased by John Goshorn in Richmond, Virginia in 1852, and later sold to his son, William S. Goshorn of Wheeling, Virginia. It was quite late into the Fugitive Slave Act crisis. The cruel Federal policy of 1850, much opposed, forced Northern free states to return escaped slaves to their Southern owners. In spite of the North’s opposition to the act, they were in theory compelled to comply, due to Southerners almost total control of the political system, a control which was broken only when the Southern states withdrew from the Union.

By January 1861, however, William Goshorn had tracked her down. With the aid of US Marshals, he had her arrested. She was defended in court by prominent lawyer and abolitionist Rufus Spaudling. Unfortunately, however, there was no defense to the slaveholder’s claims against her. Therefore the Federal Court in Cleveland was forced to rule for the return of Bagby to Goshorn. This was the last case of a fugitive slave being returned to their owners under the Fugitive Slave Act. By this point, four states had already seceded from the Union. The Republican newspaper Cleveland Leader cautioned local abolitionists to obey the law for the sake of unity. Abolitionist, African American female poet Frances Ellen Watkins criticized this sentiment, declaring in her poem To the Cleveland Union-Savers, “Ye may offer human victims, like the heathen priests of old; and may barter manly honor for the Union and for gold. But ye can not stay the whirlwind, when the storm begins to break; and our God doth rise in judgment, for the poor and needy's sake.” Watkins was correct: a few months later, Ohio and Virginia would be at war. William Goshorn, like many other Virginia slaveholders, would commit treason against the United States by voting for Virginia to secede.

Sara Lucy Bagby, ca. 1904, Cleveland, Ohio

The story of the injustices done to Bagby is sadly better known than her subsequent fate, which was altogether happier. William Goshorn would be arrested for treason ironically by his own business partner, then an Army Colonel, Benjamin F. Kelley. Bagby was sent farther South by Goshorn pending sale to Cuba, but was later freed by Union forces under Captain Vance in Fayetteville, Tennessee. It was by then 1863, and with the Emancipation Proclamation now the law of the land Bagby was at last free. She would move first to Athens, Ohio, and then on to Pittsburgh. There, Bagby would then marry Union soldier F. George Johnson. The couple would return to Cleveland in the 1880s, and lived there for the remainder of their lives. Bagby was honored at a meeting of the Early Settlers Association in 1904 at Gray’s Armory where she received a standing ovation. She would pass away only a few years later, in 1906, as a result of septicemia contracted after a fall down a flight of stairs in a home in which she worked. She is buried in Woodland Cemetery under the epitaph “Unfettered And Free.” Bagby’s story, thus, is not only one of tragedy before the outbreak of the Civil War, and a cautionary tale about unjust laws, but also a redemptive story of a woman who in spite of personal strife discovered a new home which she would return to throughout her life.

Memorable may have a rather unfortunate full title, yet it lives up to its name. Containing profiles of African American Clevelanders ranging from well known 20th century figures to the most obscure and earliest 19th century people whose lives are as much folklore as fact, the book provides not only an invaluable starting point for any research into Cleveland’s Black history, but also a snapshot of the late 1960’s and the efforts of early scholars to record and share their findings. Although much has been written on the subject since 1969, subsequent authors owe a substantial debt to the early efforts of Russel H. Davis. The focus of the work on the earliest Black history of Cleveland as well as its illustration by Black artists and its brevity make the book worthy of at least a read by both the scholar and the curious alike… even if its title is unlikely to make you want to place a copy on your shelves. Maybe just check it out from the library!

Incidentally, I am one of the scholars who is rightly in Mr. Davis’ debt. I have previously worked in conjunction with Cleveland State University on the Cleveland Green Book Project, a digital history project chronicling the guide to safe recreational spots for African Americans in the 1930s and 1940s. If you are looking for more to read during Black History Month, please check out the articles I have written there.

I also highly recommend paying a visit to the Soldiers’ & Sailors’ Monument in downtown Cleveland this month, which celebrates all of the 9,000-plus men who served in the American Civil War from Cuyahoga County, where I was previously an intern. The roll of honor there now includes the 107 members of the United States Colored Troops from Cuyahoga County. These men were added to the roll of honor in 2019, in a ceremony I had the honor of attending.

In these trying times, serious reflection and study of our history is called for. Fortunately, Cleveland offers plenty of opportunities to study our shared history and in it find clarity, guidance, and comfort. We at Dunham Tavern Museum hope that you can find the time not only to explore Black history this month, but also join us for tours Wednesdays or Sundays, 1-4 PM to enjoy the hospitality and community we have proudly offered to the public throughout our long and storied history.

Further Reading:

Autobiography of John Malvin: https://books.google.com/books?id=XvMPAQAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

Cleveland Green Book Articles:

https://greenbookcleveland.org/author/d-virostko/

Cuyahoga County Soldiers’ & Sailors’ Monument, Roll of Honor, USCT:

https://www.soldiersandsailors.com/honored-veterans/2019-additions-usct

Sources:

Davis, Russel H. , Memorable Negroes In Cleveland’s Past, Cleveland, Ohio: Western Reserve Historical Society, 1969

https://bratenahlhistorical.org/index.php/russell-davis/

https://case.edu/ech/articles/d/davis-russell-howard

https://www.newspapers.com/article/lancaster-eagle-gazette-teacher-assignme/82084158/

https://digital.case.edu/islandora/object/ksl%3A2006148021

https://karamuhouse.org/history/

https://case.edu/ech/articles/m/malvin-john

https://clevelandmagazine.com/at-home/articles/ohio-city-homeowners-renovate-a-historic-farmhouse

https://case.edu/ech/articles/t/tilley-madison

https://newspaperarchive.com/obituary-clipping-nov-05-1887-1369617/

https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/justin-holland-1819-1887/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sara_Lucy_Bagby

https://edu.lva.virginia.gov/changemakers/items/show/4

https://clevelandhistorical.org/items/show/517

https://www.clevelandcivilwarroundtable.com/the-case-of-lucy-bagby-the-last-fugitive-slave/