Old Fashioned Elections

The Role of Taverns in 19th Century Elections

Duncan A. Virostko, Museum Assistant

“Here strangers from a thousand shores, Compell'd by tyranny to roam; Shall find, amidst abundant stores, A nobler and a happier home.” ~Jefferson & Liberty, ca. 1800

Elections have been taking place in the United States since long before its inception, as part of a democratic tradition passed down to us from Greece, by way of England. You’ve probably studied the forty six presidents of the United States to some degree and how our electoral system works. You might even know something about the politics of the 19th century US, so you might have an idea of who you or your ancestors would vote for. But how much do you know about what it was like to vote back then? And did you know that Taverns played a key role in early US elections?

The landscape of nineteenth century elections was no less contentious than our own. Indeed, from nasty personal attacks to politically biased news reporting, much of it would be familiar to the present day voter. Invective, scandal, and wild accusations flew fast and free in an era when newspapers openly declared their political leanings with titles such as “County Democrat”. Elections and music too went hand in hand then as now, though 19th century election songs usually invented new lyrics to accompany familiar tunes, with the result being rather more original than a mere question as is the present fashion. Politics in the United States have always been a messy affair, a byproduct both of the factionalism George Washington warned of in his final address, and of our democratic system in general. New methods of campaigning were also developing in the early United States, with the campaign tactics we are now familiar with being invented for the first time during the period. Ultimately, although issues and beliefs have changed with time, there is much in 19th century politics and elections the voter of today would recognize.

The actual process of voting, however, would cause the modern citizen exercising their civic duty to wonder if they had wandered into the mirror universe of Star Trek!

The County Election, George Caled Bingham, American, 1854. A typical early American election. Voters declare their votes viva voce.

No doubt the first shocking difference would be how voting took place. The secret ballot, called then the Australian ballot for its origin, was not widely adopted as a method of voting until the late 19th and early 20th century in the United States. The reason for adopting the secret, and perhaps more importantly government printed ballot was to curb fraud through the ticket voting system. However, “voting straight ticket” was actually the less common way to vote in the 19th century. Rather, the most common way to vote was viva voce: by voice. Voters would ascend a platform and before election officials openly declare their votes. The feeling at the time was that this would induce people to not vote for their own selfish interests but for the common good, as they had to declare their vote in front of their community.

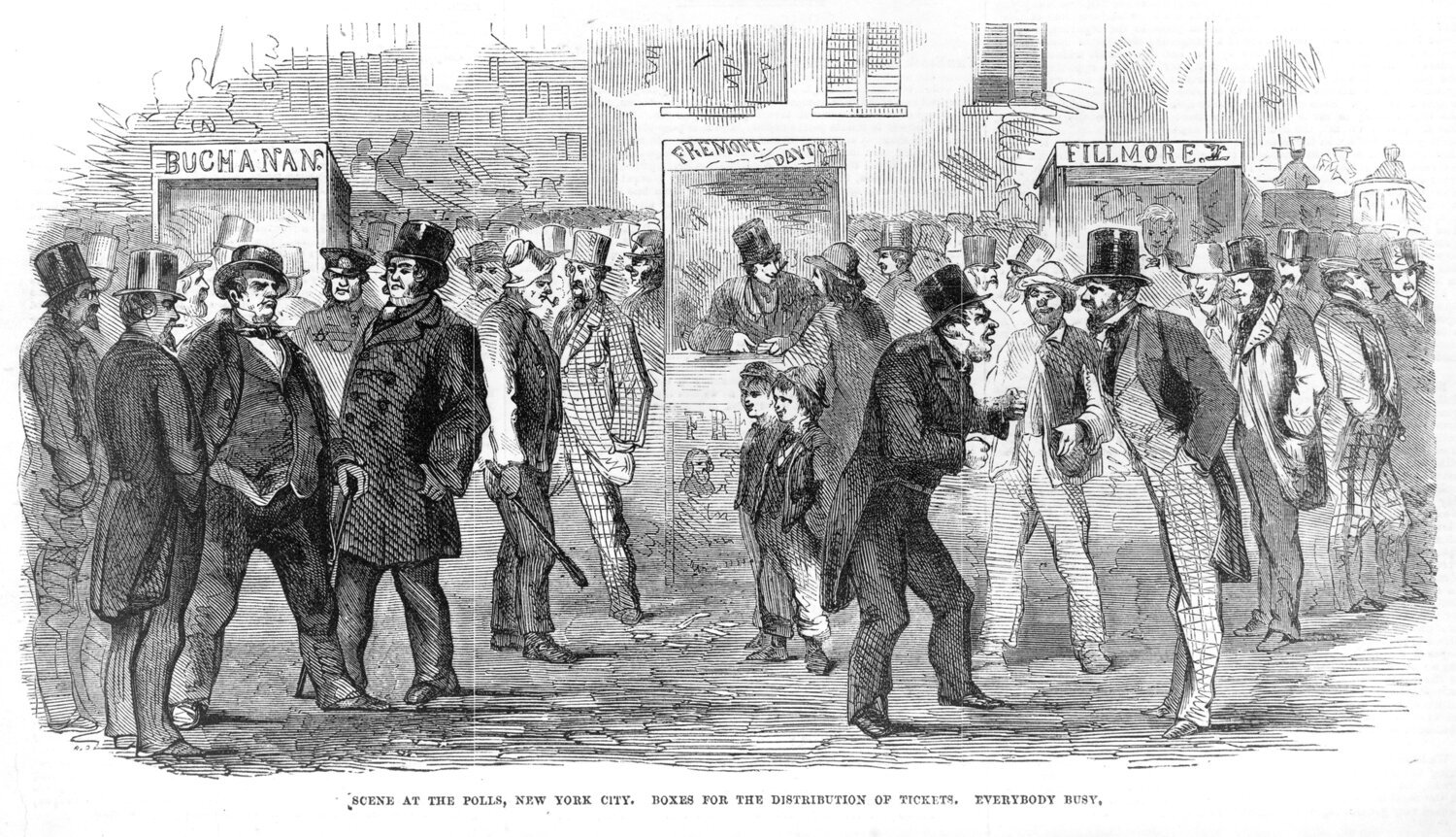

The 1856 Presidential election in New York. This cartoon shows a series of booths run by representatives of the candidates, which would hand voters their “tickets”.

Ballot Box, Glass & Iron, Mid 19th Century, American.

Patented in New York, these distinctive glass ballot boxes became a symbol for transparency in 19th century elections.

“The voter is under an absolute moral obligation to consider the interest of the public, not his private advantage,” the English philosopher John Stuart Mill opined. Americans of the 19th century also rightly regarded anything done in secrecy with great suspicion, and with the assumption that it was being done to promote “private advantage”. This was reflected in the ballot boxes of the period: often they were glass so that every voter could see each ballot cast. This was meant to prevent the practice of “stuffing” ballot boxes with fraudulent votes, which was all too easy when votes were cast using “straight ticket” ballots produced by political parties that were already filled out. Since every “straight ticket” ballot was both identical, and produced with an entire slate already voted for, it was possible to rig multiple elections in this manner and virtually impossible to tell legitimately cast votes from illegitimately cast ones.

Both types of voting, viva voce and ticket, also had the same drawback of leading to violence at the polls. Public intimidation or outright brutality could keep voters from exercising their right to vote at all or pressuring them into voting for candidates or parties that did not otherwise intend to in order to avoid reprisals from local party operatives or their neighbors. This drawback was particularly notable in the South, where racist violence kept African Americans recently enfranchised by the 14th and 15th Amendment from voting after the Civil War.

In the early 20th Century, the Australian ballot, named after the country where it was first adopted, replaced both previous forms of voting. This was essentially the modern system of voting: ballots were secret to prevent intimidation of voters, and printed by the state with all candidates to allow both for split ticket voting and to prevent political parties from from fraudulently casting votes.

The Green Dragon Tavern gave birth to the Sons of Liberty, and ultimately American democracy. Taverns would later play a large role in voting as local polling places.

Another difference was where the election was held. Unlike today, polling places tended not to be located at schools and churches, but at other public buildings. The most surprising of these to a modern voter would be the Tavern. Taverns, as often the only large public buildings in early settlements, served not just as accommodations for travelers but also as the social centers of small towns. Business would be discussed and transacted there, celebrations held, and politics discussed. Indeed, the Sons of Liberty had in the preceding century met in a Tavern called “The Green Dragon” to plot the Revolution against King George.

It was only natural, therefore, in the newly formed American republic, that country Taverns would become typical polling places. MacIllrath Tavern, a contemporary of Dunham Tavern, located at the crossroads of Euclid Avenue and Superior Ave in East Cleveland, then part of Doans Corner mile east of Dunham Tavern, served as a polling place for early Cleveland elections. Unlike today, the Election was cause for celebration, and in addition to ample whiskey, voters engaged on wresting and jumping matches, horseshoe toss and other games.

McIllrath Tavern, ca. 1860

Potent potables were, of course, a powerful inducement to vote in favor of a candidate. It was a well honored tradition for candidates to provide alcohol to their constituents in exchange for their votes. Enormous quantities of alcohol were consumed on election day by voters: George Washington once secured his reelection to the Virginia House of Burgess with “144 gallons of rum, punch, hard cider and beer his election agent handed out—roughly half a gallon for every vote he received.”! Taverns and other establishments were only too happy to take their business. Of course, this way of winning votes was easy to abuse: “Cooping” was the practice of unscrupulous party hacks kidnapped a victim, then plied them with alcohol and drugs. Using a series of disguises, they then proceeded to use the semi-conscious victim to impersonate multiple voters at several different polling stations. Clearly, arriving at a polling station an entire clipper before the wind was no disability to having one’s vote counted! Shortly before he died in October 1849, Edgar Allen Poe was found collapsed in Baltimore outside a polling place, heavily intoxicated, and it was suspected that he had become a victim of this practice. Other historians dispute this, however, attributing Poe’s death to chronic alcoholism instead.

Edgar Allen Poe may have died of alcohol poisoning due to being drugged in an election fraud of the 19th century known as “Cooping”.

We do not know if Rufus Dunham’s tavern ever served as a polling place. For much of its existence, the Tavern was somewhat remote from Cleveland proper, and the Dunham’s had few neighbors. This probably would have precluded its use as a polling station: there was no surrounding community to serve, only forest and wolves. And wolves don’t vote!

We do know, however, that until 1827 it was common for Rockport Township, centered on present day Rocky River, candidates to provide free whiskey to voters, the so called “jug ticket”! This tradition was broken however by Datus Kelley, who ran a one man temperance ticket that year.

The actual process of voting has changed to such a degree since Rufus Dunham’s time, that is is nearly unrecognizable to the voter of today. We no longer insist upon voters making their votes in person, vocally, in front of an assembly of their peers. Although we perhaps still share a suspicion of secrecy, the Australian style secret ballot is now the norm, as a result of reforms enacted at the end of the 19th century to eliminate the ticket system of voting which was often abused by political operatives. Equally, as our communities have grown and changed, we have found less boozy public places to make polling places than Taverns, bringing the end of those establishments that once played a central role in politics. Although we may still drink something on election day, especially if things are going poorly for our chosen party, we generally do so after we’ve voted. This is a great contrast from the central role alcohol once played in getting out the vote, with candidates garnering support through offering free drinks to sometimes unwilling voters. Fortunately for our elections, and unfortunately for Edgar Allen Poe, subsequent reforms brought an end to that tradition in the 20th century. As strange as past election practices may be to the modern voter, they reflected an era where popular elections themselves were new and exciting. The 19th century saw an ever increasing number of people gain the right to vote, and be able govern themselves, and so the process of voting was ever evolving.

Election Cake Recipe, American Cookery, 1796

Some early voting traditions, however, perhaps could stand a revival. In the early United States, it was traditional to serve Election Cake on election day, a sweet treat to buoy the patriotic spirit. The recipe for the cake was first published in American Cookery by Amelia Simmons in 1796, though its history dates back to the Colonial period. It was later also shared in The American Frugal Housewife, by Ladia Maria Child published in 1834, copies of which are in the Dunham Tavern Museum’s library collection. Why not try your hand at recreating this delicious cake, using the recipe shown here?

Sources:

Rose, William G, Cleveland The Making of A City, Cleveland, Ohio, 1950

https://www.untappedcities.com/boozy-history-voting-bars-election-day/

https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2016/fall/feature/back-when-everyone-knew-how-you-voted

https://www.roosevelthouse.hunter.cuny.edu/seehowtheyran/portfolios/origins-of-modern-campaigning/

https://northshoredistillery.com/taverns-as-places-of-public-discussion/

https://hylandhouse.org/at-home-activities/bake-a-historical-election-cake/