Sun & Shade

A Dunham Tavern Exhibit Spotlight

By Duncan Virostko, Museum Assistant

Sun & Shade, An Exhibition of the Parasols of Dunham Tavern Museum & Gardens, Spring 2025

Why is pongee like a pursuit plane? The answer is parasols!

Dunham Tavern museum is blessed with a small, but lovely, collection of parasols from the end of the 19th and dawn of the 20th century. When trying to decide the subject of the special exhibit for the beginning of 2025, I settled upon parasols in the hope that it might induce some sun to finally break the bleak winter that has seemed to drag on far too long, as per usual.

You might well ask what exactly a parasol is in the first place? What does the word even mean?

The word parasol itself derived from the Latin parare meaning shield , and sol meaning sun. In French, this became parasole, which became an English loan word. Umbrella also comes from the French word ombrella, which in turn comes from the Latin umbra meaning shade.

Parasols have been in use as shields against the sun for millenia. The familiar fabric parasol was developed in Ancient Persia, now Iran, sometime before 2310 BCE. The parasol was first introduced to Western Europe by the Ancient Greeks in the 8th century BCE. The Romans subsequently adopted it, and it became largely a ceremonial and religious object. It was not until well into the Renaissance, sometime during the 1570s CE that the Parasol made its way to France from Italy, and thence to England, as an item of fashion for ladies.

The first umbrella company in the United States was the Beehler Umbrella House of Baltimore, Maryland, established in 1828 by German immigrant Franz Beehler. Baltimore would go on to become a major production center for parasols and umbrellas in the United States, shipping out 1.5 million annually during the 20th century. The Ganz company, a Jewish owned competitor to Beehler founded in 1888, popularized the advertising slogan “Born in Baltimore, Raised Everywhere!” to promote its wares. Ironically, however, the slogan later became associated with Beehler. Some Baltimore companies, such as Crown Brand and Siegel, Rothschild & Co., even specialized exclusively in ladies parasols, so high was the demand at the turn of the century.

That demand was the result of an innovation in parasol design. Steel framed parasols were developed in the 1840s. Previously, parasols had been made with wooden frames which were delicate, yet heavy, and required skilled craftsmen to produce. The new steel framed parasols in contrast were lighter weight and more durable than previous designs, and could be produced en masse using machine tools. Thus, the industrial revolution made such fashion accessories readily available and affordable to middle class women. As a result they became not just items of high fashion but everyday objects, commonly used by American women.

The parasols on display from Dunham Tavern’s collection date from the 1890s to 1900s, the height of the parasol as a fashion. Oiled silk or lace are used for their canopies, and their handles are made of wood carved into intricate shapes. The details of their designs are expressions of both the status and personal styles of their owners.

Much of the collection is the gift of one Mrs. Richard Cross, a member of the Dunham Dames, a women’s auxiliary of the Society of Collectors which ran Dunham Tavern from the 1940s until the 1980s. The Dames were, in fact, far from auxiliary, being largely responsible for giving tours at the museum and funding the restoration of several rooms on the second floor of the Tavern. Many devoted their own time, effort, and money to care for the museum and its grounds. Naturally, being antique collectors, they also donated many of their own artifacts to the museum, and probably facilitated the donations of others as well.

743.G Brown Parasol with Black Lace, ca. 1890

The first parasol on display in Sun & Shade is one of the earlier, and simpler examples in the collection. Dating to approximately the 1890s, the handle and shaft of this parasol are comparatively simple and naturalistic compared to others in the collection. It consists of a straight wooden handle, with vine-like carvings that create a sleek and elegant look. This contrasts with the elaborate fabric covering of the parasol, which is a brown embroidered silk, trimmed with black lace. A black silk ribbon sewn around the tip or ferrule lends the parasol a decidedly girlish touch.

Although dark colors like black in 19th century fashion are popularly associated with the complex mourning rituals of the period, this parasol demonstrates that is not always a valid assumption. The black and brown color of this parasol served a more functional purpose: it would have been opaque to and completely blocked the sun’s rays. Other parasols, of lighter colors, would be less effective at this purpose, and thus were a deliberate fashion choice at the expense of practicality. The same holds true, incidentally, for women’s bonnets of a slightly earlier period that are one display at Dunham Tavern. Designed more to protect women’s hairstyles from dirt and wind while traveling, bonnets actually provided little in the way of shade for women, and were therefore often worn with a black lace veil pinned to the front of them to shield their eyes. Bonnets of a darker color would help block some of the sun’s rays, but equally suffer from absorbing their heat. Simply because a piece of 19th century women’s fashion is black does not necessarily mean it is for mourning. Sometimes, it’s just to keep out the sun!

744.G Parasol with Black, White, & Blue Stripes, ca. 1900

The second parasol on display is of a slightly later date, from approximately the turn of the century. It features a smaller size of cover that contrasts with its quite long straight handle and ferrule. These are also made of wood, a straight stick elegantly shaped but still keeping its natural form. Unlike the proceeding parasol, its handle does not feature any carvings and instead is left plain. However much like the first parasol in the exhibit, the bulk of the fashionable design has gone into the silk covering. This features striking white, black, and pale sky blue stripes in a tartan pattern. By this period, the parasol had reached its ultimate form and popularity in women’s fashion. During World War One, the fashion would shift towards rain-proof umbrellas, made largely for men and the parasol would fall out of fashion for women. Possibly this represented a shift towards practicality, born out of the wartime austerity, as this ultimate form of parasol with its light color and smaller canopy was certainly less practical than earlier examples of parasols at blocking the sun. Thus, it was largely an ornament of fashion, one which might be dispensed with easily with changing trends.

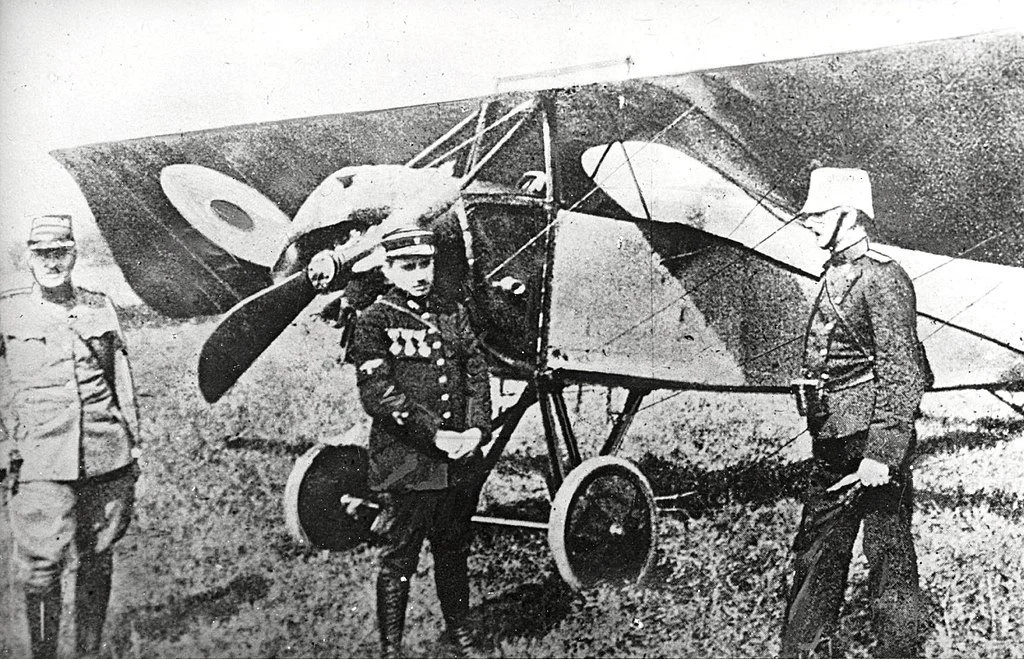

Morane-Saulnier L in French markings. (San Diego Air & Space Museum Archives)

Ironically, as parasols went out of fashion for women, they came into fashion amongst aviators, with the invention of the parasol wing airplane. Parasol wing planes are a type of single wing, or monoplane, which have their wings supported by struts above the main body or fuselage of the aircraft. Initially developed at the beginning of World War One as observation planes with improved downward visibility, they soon evolved into high-speed fighter aircraft. An excellent example of the type is shown above: the Morane-Saulnier L of the French Air Force, one of the most capable fighters of 1914 that helped defeat the infamous “Fokker Scourge” of German air superiority. Monoplanes had advantages over biplanes and triplanes of WW1 as fewer wings meant they had less drag and so could achieve higher straight line speeds. But they often had weaker structures than biplanes, and had lower climb and turn rates, both useful in dogfighting. Parasol airplanes' designs mitigated some of these issues, largely by having stronger structures closer to contemporary biplanes, where the wing was built as one large piece rather than two pieces and attached to the fuselage of the aircraft. This stronger structure meant that they were more resistant to battle damage but that they also were more maneuverable than other monoplanes, as they would not break apart under stress from violent maneuvers. Parasol airplanes would continue to evolve after the war, and reached their heyday during the 1920s and 1930s. Incidentally, during this period the United States Army Air Corps referred to fighters as “pursuit” planes, designating them with the letter P and their model number, such as the P-26. As aircraft evolved from having fabric covered skins supported by wooden or metal ribs, to having metal skins that were load bearing during that time, many of the advantages of the parasol wing design evaporated. Thus, by World War Two, the Parasol wing monoplane was rendered obsolete.

Today, two Parasol fighter planes survive in the collection of the superb Old Reinhbeck Aerodrome museum of Red Hook, NY on static display, a 1917 Morane-Saulnier A-I, and a 1932 Morane-Saulnier MS.130, both continuations of the line of fighter development started in 1914 with the L model. In addition to static exhibits of these and many other pioneering aircraft, the Reinhbeck Aerodrome also hosts airshows every Saturday and Sunday June 14-October 19.

736.G Tan Pongee Silk Parasol with Burl Handle, ca. 1890, Gift of Mrs. Richard Cross

The third parasol in the exhibit, dating from the 1890s, presented me with a question when I was working on curating this exhibit, and found its description in the accession records: what in the world is pongee!?

Pongee is a special type of woven silk, produced in China, which was heavily exported in the late 19th century and early 20th century to the United States. It is slub woven, meaning that it is woven from the shorter fibers of silk removed in combing which would otherwise be waste, known as slub. The result is a cheaper type of silk with a pronounced texture. Pongee was produced in mills along the Yangtze river, which the United States policed as part of the unfair “Open Door” policy of colonialism in China.

The cover of this particular parasol is made with a gold coloured pongee of intricate design, trimmed with black silk ribbon. An elegant tassel of the same color as the pongee is wound around the handle of the parasol, and adds an unique touch to the ensemble.

This particular parasol is the first of three featured in this exhibit donated by Mrs. Richard Cross, and is remarkable not just because its cover is made from pongee, but also because of its unique handle. The wooden handle of the parasol has a unique knobbled look, and a pronounced pommel in contrast to the completely straight handle of the preceding examples. This was accomplished by craving the handle out of a branch with burls, or growths which form in some tree’s wood from dormant buds, and also by fitting a larger burl as the pommel. The idea, perhaps, was not only to create a unique looking handle but one which would not easily slip from the hand. In anycase, clearly, the owner of this parasol felt the finer things in life must also have texture!

738.G Silk Lined Lace Parasol with Carved Maple Handle, ca. 1890, Gift of Mrs. Richard Cross

737.G Brown Lace Parasol with Carved Maple Handle, ca. 1890, Gift of Mrs. Richard Cross

The final two parasols exhibited in Sun & Shade are a pair of parasols which are very much alike. Differing largely in color, they both date from the 1890s and once again belonged to the collection of Mrs. Richard Cross. Both are made entirely of partly translucent lace, one a brown color and the other a cream color. Such designs certainly would have been cool in the summer due to their airy material and reflective colors, but because they were translucent would not have been as effective at shielding their owners from the sun. Thus, they are more objects of fashion than practicality. The cream-colored parasol somewhat overcomes this objection, however, by being lined with an opaque silk of a lighter color to help block the sun. Like the pongee parasol, it also features a tassel attached to its shaft, which also has a faint pink color to it. No doubt, this parasol once was part of a charming spring or summer outfit, in white with pink accents as was a popular style of the time. Perhaps it saw use on romantic picnics in a park or for Easter Sunday outings.

Both parasols also exhibit finely carved maple handles, with their ends shaped in a looping form. The cream colored example is by far the more complex of the two, featuring an organic motif in its carvings, with a finial shaped like a leaf. Amusingly, in spite of being made of maple, the spade-like leaf which forms the finial is decidedly closer to an oak leaf than a maple! Oak, being a harder and heavier wood, would presumably have made a poor choice for a carved handle of a delicate parasol. In contrast, the brown covered parasol shows rather more primitive carvings. Its finial, rather than being short and flattened as in the case of its counterpart, is instead long and cylindrical in form, with three ribbed bands its most prominent feature. As a result, it gives a rather war-like impression, reminiscent of the lance of a knight errant. The idiosyncrasy is probably accidental, and would likely not have been particularly noticeable when the parasol was raised. This illustrates an interesting point in the artistic design of parasols: they are by their nature a sort of kinetic sculpture with a practical purpose. Their complexities in design thus speak to the abilities of their designers to create fashionable shapes in two different forms of existence: furled and unfurled. It was no small task.

The use of parasols for fashion is intrinsically tied to beliefs which hold whiteness as a sign of beauty, and high social status. These beliefs were the result of racism, colorism, and classism in the 19th century, and sadly still persist today. Historically, whiteness or paleness of skin tone has been associated with being a member of a society’s upper class, who did not need to work in agriculture or outdoors and thus were less tanned than the lower, working class. This belief was one which many cultures developed independently, without contact with later European racial views— something Western commentators are prone to miss. Japan, for example, developed the heavy white makeup used by Geisha for this reason, long before they had contact with the West.

By the 19th century, such views were not only relatively universal but strongly solidified across numerous cultures. These preexisting beliefs then collided with the newer development of 19th century racist and colorist beliefs. Under newly developed pseudo-scientific belief systems, light skin tone came to denote not just social status, but a biological and moral superiority over others. Such belief systems saw skin tone as intrinsic—forgetting entirely the existence of not only the existence of persons of mixed or ambiguous race, but also makeup. Such beliefs belie the misogynistic world views which underpinned them: the men who conceived them could not conceive of using products to make one’s race ambiguous. For persons of color, existing beliefs about status and lightness of skin tone along with imposed beliefs of racial superiority of lighter skinned people created colorism, the belief that lightness of skin tone even as a person of color confers privilege to that person, which lead either to attempts to “pass” for a lighter skinned person or hostility towards people of color with lighter skin tones.

It is in this context that parasols, a fashion item that shielded the user from the tanning rays of the sun, existed and reached their peak popularity. During the 1800s even freckles caused by sun exposure were considered an unsightly blemish, so fashionable ladies had to constantly shade themselves. Wearing makeup at the time was considered socially unacceptable, so the women often purchased and applied their cosmetics in secret. These often contained harmful substances, such as white lead to lighten skin or arsenic to remove freckles, which were detrimental to their health. The danger was known, but overlooked for sake of beauty. Using makeup was thus a fraught proposition for the 19th century woman. A parasol, by contrast, was not only socially acceptable but a fashion statement, and achieved the same practical purpose without risk to one’s health.

There were of course practical reasons for shading oneself too. Without modern sunblock, the only way to prevent skin cancer after prolonged sun exposure was to directly block it. This is the reason that the summer fashions of the 19th century, whilst featuring lighter colored and weighted fabrics, were not any shorter than clothes for cooler weather, and why broad brimmed hats were fashionable for both men and women. A short sleeved garment would be largely impractical to wear outdoors, and thus usually only appear on women’s ball gowns. Although it was considered uncouth for men to wear only a shirt, it was not uncommon amongst lower class men engaged in hard physical labor. Hot weather and hot work of course sometimes compelled them to strip to their waists… but this in turn invited the potential of skin cancer. Thus, even in the heat of summer the average middle class Victorian man or woman would have worn more clothes than we would now find comfortable, simply as protection from the sun.

Ultimately, the parasol as an object is a fascinating intersection of history. On one hand, it is a marvel of technology and industrialism, a formerly luxury good made abundant as the 19th century fuel increased living standards in the United States. It is a story of a bygone American industry, which grew exponentially as new technology allowed immigrant founded and operated businesses to prosper and shape the culture of Baltimore, Maryland and other centers of the parasol-umbrella trade.

From a different perspective, the very necessity of blocking the sun from ones’ skin represents the juncture of pernicious ideologies around both human worth and beauty. They are to a degree classism, colorism, and racism made manifest, in the form of an object whose usefulness attests the everyday evil of those ideologies. Even the materials used in covering a parasol can be a reminder of the United States dabbling in colonialism in Asia during the late 19th and early 20th century. The rarity of the parasol in the present day also tells us something about the changing social climate of the 20th century, when it fell out of fashion.

From these larger contexts, we can extract a parasol and examine it as an individual artifact, an object of fashion which tells us about the social status, needs, desires, and artistic sensibilities of its owners purely through its form and aesthetics. What sort of woman would have carried a small and elaborate lace parasol? How might she have been different from a woman who carried a larger black parasol?

Sun & Shade raises and attempts to answer these questions, through an examination of Dunham Tavern’s collection of 19th and 20th century parasols. We invite visitors to come see our new special exhibit in person here at Dunham Tavern Museum & Gardens. The exhibit is unique in offering guests the ability to intimately examine these rare and fragile artifacts: at five artifacts total it may be one of our smallest exhibits yet, but they must be seen firsthand to be truly appreciated!

Sources

Simpson, Elizabeth, "A Parasol from Tumulus P at Gordion", Armizzi. Engin Özgen'e Armağan / Studies in Honor of Engin Özgen, 2014: 239

http://margaretroedesigns.com/wp-content/uploads/ParasolHist.pdf

https://preservationmaryland.org/made-in-maryland-the-first-umbrella-factory-in-baltimore-city/

https://www.foxumbrellas.com/pages/fox-umbrellas-ltd

Davilla, Dr. James J.; Soltan, Arthur. French Aircraft of the First World War. Flying Machines Press, Mountain View, CA, 1997

Taylor, Michael J. H., Jane's Encyclopedia of Aviation. Studio Editions, London, 1989

Green, William and Gordon Swanborough. The Complete Book of Fighters. New York: Smithmark, 1994.

Angelucci, Enzo. The Rand McNally Encyclopedia of Military Aircraft, 1914-1980. San Diego, California: The Military Press, 1983.

Bruce, J.M. Morane Saulnier Type L - Windsock Datafile 16. Herts, UK: Albatros Publications, 1989.

https://oldrhinebeck.org/morane-saulnier-a-1/

https://oldrhinebeck.org/morane-saulnier-ms-130/

https://oldrhinebeck.org/airshows/

https://prestonparkmuseum.co.uk/victorian-beauty/

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/23091-freckles

https://thesciencesurvey.com/spotlight/2022/04/24/skin-color-and-beauty-standards-a-history/